clean air car test ontario

The good news: Ontario is scrapping its $30-fee for mandatory Drive Clean emissions tests on vehicles seven years and older, starting next year.The bad news: motorists still have to get the checkups and pay for any necessary repairs to meet the standards, keeping smog-causing pollutants out of the air and reducing greenhouse gas emissions.Finance Minister Charles Sousa said the break is intended to make “everyday life easier” for citizens, who will also be forking out an average of 4.3 cents more per litre of gasoline as the fight against climate change ramps up.The Drive Clean program, started in 1999 by the Mike Harris Progressive Conservative government, has long been a target of critics who called the testing a cash grab. That prompted a $5 reduction in the fee a couple of years ago.Taxpayers will now be reimbursing garages for the tests — about two million are conducted annually at a cost of $60 million.Conservative Leader Patrick Brown said getting rid of the fee is “a good start,” but it’s time to scrap the Drive Clean altogether.

Motorists with older vehicles won't have to pay for Drive Clean tests, but they'll still have to get the check-ups and pay for any necessary repairs to meet the standards.)“

air purifier kills flu virusA lot of people have found ways around that program.”

air purifier vs plantsSousa pledged to continue reviewing Drive Clean as cleaner fuels and improved exhaust technologies come to market.

air duct cleaning marketing planSince its inception 17 years ago, Drive Clean is credited with keeping 335,000 tonnes of pollutants out of the air.In all, vehicles account for about one-third of greenhouse gas emissions.:Ontario budget lowers post-secondary tuition while hiking gas costsCrunching the numbers in Ontario's 2016 budgetOntario cracks down on underground economy, goes after tax cheatsWhat the 2016 Ontario budget means for youMore from the Toronto Star & Partners

Ontario to drop $30 fee for ‘Drive Clean’ tests Starting in 2017, Ontario drivers of older vehicles will no longer have to pay $30 for their biennual “Drive Clean” emission tests. It is still unclear how Drive Clean facilities will be paid for conducting the two million tests that are conducted annually. The Automotive Industries Association of Canada has said it has been in touch with the provincial government to ensure repair facilities are still compensated fairly for the tests. “At this time, details surrounding payment logistics and timelines are not available and AIA plans to work closely with industry and the Ontario government to ensure that members are informed and well prepared for this program transition,” the association has stated. The Liberal government of Premier Kathleen Wynne has announced it will eliminate the fee to help offset the additional cost consumers pay at gas pumps – calculated to be an average of 4.3 cents per liter.

The additional revenue from gasoline sales will go to measures intended to protect the climate. The emission tests will still have to be conducted on vehicles seven years and older, and emissions-related repairs will still need to be done. In a statement from the province, the elimination of the fee is said to be one of several measures intended to “making every day life easier” for Ontario residents. Other measures, cited by Finance Minister Charles Sousa are lowering hospital parking fees for frequent users, helping with electricity and energy costs, reducing auto insurance rates, and using technology to more conveniently deliver public services. The Drive Clean program was launched in 1999 by the Mike Harris Progressive Conservative government, and is credited with keeping 335,000 tonnes of pollutants out of the air. Initially, the tests carried a fee of $35 but public criticism that depicted the program as a cash grab led to a $5 reduction. Conservative Leader Patrick Brown said getting rid of the fee is “a good start,” but it’s time to scrap the Drive Clean altogether.

Auto 7 expanding into Canada: report Date set for Women’s Leadership Conference 2016This past December, British Columbia wound up its AirCare program, which for 22 years had been doing mandatory testing of vehicle emissions. Higher industry standards meant failure rates were few, and the province concluded the program had served its purpose. Ontario, on the other hand, decided the same diminishing failure rates didn’t really justify a biannual badgering of its citizens who owned vehicles older than seven years, so it would instead change the emissions testing to flunk more cars. It’s not quite that simple, but it sure feels like it is. Introduced in 1999 by the Ontario government, “Drive Clean” was initially meant to weed out vehicles belching unrestrained amounts of exhaust fumes, their particulate emissions contributing to smog and increasing pollution. More than 15 years later, there have been huge reductions in emissions, but those gains are overwhelmingly the result of advances in technology — so long, carburetors — and cleaner fuels.

And even though the costs for taking the tests (sometimes repeatedly) are still borne by taxpayers (not to mention the time), the program makes barrels of money for the Ontario government. According to a 2012 Auditor General’s report, the program — which is supposed to be revenue neutral — turned a surplus of $11-million in 2012. It’s targeted to have a surplus of $50-million by 2018. Since its inception, the Drive Clean program has been more thorns than roses. Initially requiring tests on cars every second year once they were just three years old, it was soon nudged to cars over seven. Every two years, owners have to arrange a visit to an accredited Drive Clean facility and pay $30 (it used to be $35) to get a clean bill of health. Any car under seven years old, unless it’s the current model year, must also be tested if it is being sold — even those that are essentially brand new. Read more: Ignore that check engine light at your own peril According to George Iny, president of the Automobile Protection Association (APA), “failure rates for cars less than 10 years old are now below five per cent.

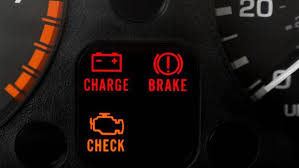

That means 20 vehicles are inspected to identify one bad one – it costs over $700 to pick up a polluter. For vehicles less than seven years old, the cost is in the thousands of dollars to pick up a problem, as only one to two per cent of vehicles fail for legitimate reasons.” The test was changed in January 2014 from a tailpipe emissions test to one that now reads your on-board computer. This change narrowed the margins for a pass and resulted in an increase in failures, a bump from the previous five per cent to eight to 10 per cent, depending on whom you ask. Cars built from 1988 to 1997 still use the older tailpipe testing method; model years before 1988 do not need to be tested. A failed test means you can’t renew your vehicle registration until it’s made to produce cleaner exhaust. The Drive Clean test reads the emissions computer OBDII (on-board diagnostics) system; as you drive, your computer cycles through numerous self-tests and stores that information. The problem is your car won’t be in test mode if the battery was recently disconnected, drained or boosted, or your computer codes were cleared during a recent repair.

If an emissions reading can’t be obtained, you’ll be told to go drive around for a few days and essentially build up a user history – get your car to run through a complete drive cycle. Of course, the questions are many: • My engine light is on. Will I pass the Drive Clean test? While there are ways to turn the light off, they will all erase the emissions data that the test must measure. I’ve heard of people putting a piece of tape over the light because it bugs them; this will not fix the problem. Do yourself a favour though: if your light comes on, check your fuel cap. Sometimes it’s simply not closed properly. • The next step is a diagnostic test to tell you what is triggering the engine light. This will cost about an hour of shop time, usually about $75 to $100. • If the required repairs exceed $450 (including the diagnostic), you can request a waiver for repairs above that amount and punt your problems down the line until the next inspection, in two years.

• “There is no environmental benefit from issuing a waiver to a polluting vehicle,” says Iny. We’ve come full circle on the biggest problem of the Drive Clean program. Eli Melnick is the owner of Start Auto in Toronto. “The intentions of the program were good,” he notes, while acknowledging that it’s execution has hobbled much of it. “When pollution controls were introduced in the late 1970s, many were clumsy and people were disconnecting and circumventing them as soon as they could.” People were disabling them as fast as the EPA could make manufacturers install them. Reduced power and reduced fuel efficiency among other things had people sawing out catalytic converters and connecting a pipe instead, says Melnick. Also read: Seven of the worst things you can do to damage your car “The program initially played a significant role in getting heavy polluters off the road. The problem is that fixing emissions problems on a vehicle doesn’t have a high perceived value;

the car might not feel any different, so people don’t want to deal with it.” The environmental impact is enormous, he notes, but a car that won’t run is far more likely to get you to fix it then one that is emitting something you can pretend isn’t there. When your engine light comes on, it is always a signal that something is wrong in your car’s emissions system. So is that sufficient for making people deal with the issue? “As long as a car starts and goes, you wouldn’t believe how many people will just keep driving. That engine light fail on the Drive Clean test is sometimes the only way to get people to repair leaky pipes, rusty gas tanks and evaporative emission control (EVAP) systems.” Melnick explains the light can come on for a hundred different reasons (up to two hundred in some cars) and the initial reason could be hiding other, bigger problems. “The light doesn’t shine any brighter to indicate more than one issue,” says Melnick. Like Iny at the APA, Melnick cites the conditional waivers as a major negative issue.